New York Times critic Bosley Crowther was utterly perplexed by Gilda on its premiere in March of 1946, not an unusual state for him.

"It is quite all right to make a character elusive and enigmatic in a film—that can be highly provocative—providing some terminal light is shed. But when one is conceived so vaguely and with such perplexing lack of motive point as is the dame played by Rita Hayworth in Gilda, the Music Hall's new film, one may be reasonably forgiven for wondering just what she's meant to prove, for questioning, indeed, the whole drama in which she is set. And that is what we frankly do.

Despite close and earnest attention to this nigh-onto-two-hour film, this reviewer was utterly baffled by what happened on the screen. To our average register of reasoning, it simply did not make sense. "

He was particularly dissatisfied with Rita Hayworth, whose charms somehow failed to interest him:

"Miss Hayworth, who plays in this picture her first straight dramatic role, gives little evidence of a talent that should be commended or encouraged. She wears many gowns of shimmering luster and tosses her tawny hair in glamourous style, but her manner of playing a worldly woman is distinctly five-and-dime. A couple of times she sings song numbers, with little distinction, be is said, and wiggles through a few dances that are nothing short of crude."

Writing a couple of weeks ago in The Observer, though, Phillip French sees what Crowther could not, the fantastical sexual subtexts that make Gilda so much fun:

"The movie revolves around the exotic Rita Hayworth and was produced by Virginia Van Upp, the most powerful woman at Columbia, who was charged by tough studio boss Harry Cohn with supervising the star's career. Hayworth is stranded in Buenos Aires at the end of the second world war, trapped between her sadistic, middle-aged husband, the Nazi-sympathiser Ballin Mundson (George Macready), and her ex-lover, the cruel, amoral American adventurer, Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford). The men have a homoerotic love-hate relationship. After Johnny sees Ballin's phallic sword-cane the first time they meet, he says admiringly: 'You must lead a gay life.'"

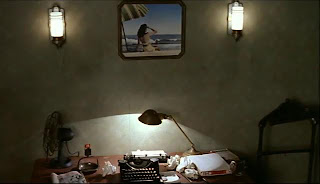

The excellent film noir podcast series "Out of the Past", hosted by academics Shannon Clute and Richard Edwards, devoted its 40th episode to Gilda, focusing in particular on the visual style of the film and the work of celebrated cinematographer Rudolph Maté.

"From the flip of her fiery hair to the reprise of her incendiary song, she sizzles the celluloid and burns herself indelibly into our collective consciousness. In fact, her presence so scorches that we are apt to miss the technical artistry of this film. Rudolph Maté's superlative cinematography uses banal objects pedagogically, to teach us to read the images: the blinds in Mundson's office make us aware of the fact we're looking, then show us how and where to look; the elaborate staging and framing of staircases make us wonder whether each character's fate is ascending or descending. While the Triad of superb players (Hayworth, Ford, and Macready) fleshes out the elaborate story, it is Maté's camera that builds the suspense. In then end, the cinematography combines with lines of dialogue pronounced by philosopher Uncle Pio to give us the world through noir-colored glasses—a "worm's eye view" that lends Hollywood's biggest stars a distinct earthiness."

Finally, Rita Hayworth is pretty. The Rita Hayworth: The Love Goddess site has the hundreds of pictures to prove it.